Sourced and translated from Mizuki Shigeru’s Hyakumonogatari, Kaii Yokai Densho Database, Japanese Wikipedia, Yokai Jiten, Nihon Kokugo Dai-ten, and Other Sources

If you have been a bad person all your life, your troubles are not over when you are dead. During your funeral procession, as the priest and the mourners carry your coffin there is suddenly a crack of thunder and roaring from the sky to steal your dead body and drag it to hell comes … what? A flaming chariot? A cat demon? A cat demon riding a flaming chariot?

Or maybe you have just died at home, and your once beloved house pet thinks that your sin-ridden body would make a delicious snack.

Kasha are one of the most confused of Japan’s yokai. Over the centuries kasha have evolved from a fiery cart pulled by devils to an aged cat that changes form into a corpse-eating monster. Even the calling them yokai is dubious. Although yokai can be a catch-all term for Japan’s monsters, the kasha are more properly demons. They have more in common with Hell-dwellers like oni, and are found on Kamakura period Hell Portraits designed to terrify people into following the righteous path of the Buddha.

What does Kasha mean?

Kasha uses the kanji火車 which translates easily as Fire (火) chariot (車). The kanji can also be read more explicitly as hi no kuruma (火の車 ) meaning the same thing.

That’s the easy part. Now what is a kasha? That’s the hard part.

Kasha – The Fire Chariot

During the Kamakura period (1185–1333), there was an apocalyptic belief in mappō, meaning the Latter of the Days of Law. Like some Christians today, Buddhist believed they were living in End Times and had no more life times in which to which to redeem their souls; they were stuck between Hell and redemption by the Amida Buddha. This lead to a form of art called Hell Scrolls (地獄草紙; Jigoku Zoshi), which depicted the painful suffering awaiting those who didn’t hurry up and get saved.

Most of these paintings depicted oni tearing people apart and feasting on their body parts. And sometimes these oni carried these poor bodies in flaming carts. The belief eventually developed that oni crawled the Earth looking for sinners and piled them in flaming carts or chariots to drag before the dread judge of Hell Emma-O.

As with much Japanese folklore, the image of the flaming chariot took a nap while Japan fought the massive civil war known as the Sengoku era, and was re-awakened during the Edo period yokai boom. Stories began to appear in kaidan-shu collections of the kasha, or hi no kuruma, a flaming cart that descended from the sky. The cart was said to be accompanied by thunder and great winds, and a funeral procession where thunder was heard raised an alarm that the kasha was coming.

The role of the kasha was undecided early on. In the early Edo period book Kii-zodanshu (奇異雑談集; 1687; A Collection of the Idle Chat of Mysterious Things) there is a story called “The Thing that came from the storm clouds to steal a corpse in the Manor House near the rice fields of Echigo.” During a funeral procession there was a loud clap of thunder and a beast riding a flaming cart came down from the sky and snatched the dead body. An illustrator depicted the kasha as being ridden by Raidin, the Shinto deity of thunder and lighting.

Another story, from Shin Chobun-shu (新著聞集, 1749, New Tales of Things Known the World Over) called “Saint Neyo and a visit from the Kasha,” had the Buddhist saint Neyo come out to meet the flaming chariot. But instead of a messenger from Hell, it was an ambassador from the Jyodo Pure Lands. The saint begged the kasha for a little bit more time on Earth, and the cart came back exactly a year later to take him to the Pure Lands.

All of the appearances of this kasha were heavily influenced by Buddhism. Most of the stories follow the same theme; a flaming cart that snatches up the bodies of those who have accumulated a lifetime of misdeeds. To protect these bodies from kasha, priests placed rosaries around the necks of the dead bodies, although that was no guarantee. Some said that the kasha was either a messenger of the divine or the infernal depending on the karmic state of the dead body.

Kasha – The Corpse-Eating Cat Demon

So how did this flaming cart from the sky become a cat?

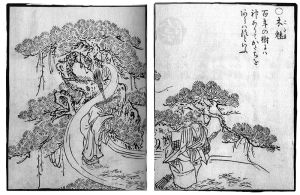

Like much with yokai, the origin of the cat-like form of kasha is said to come from artist Toriyama Sekien. When Sekien drew a kasha for the second volume of his Gazu Hyakki Yagyō (画図百鬼夜行; “The Illustrated Night Parade of a Hundred Demons) in 1776, he drew the bizarre cat-demon covered in flames. Like his spiritual successor Mizuki Shigeru, Sekien often blended his own imagination in with folklore, and simply invented things as well. He didn’t begin to add notes to his yokai prints until the successive volumes, so we don’t know why he chose to make the kasha a cat.

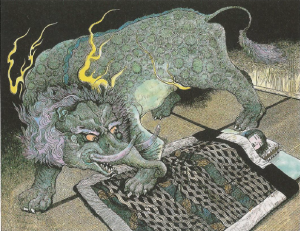

For whatever reason, Sekien’s influence on yokai was so profound that people accepted the cat-like kasha and the stories began to follow. In Boso manroku(茅窓漫録; Random Talk of Outside Cogon Grass, 1833) a typical story was told of a funeral procession interrupted by a mighty wind and thunder that swept away the coffin as a kasha came down to retrieve the corpse. This kasha was not the flaming chariot however, and was identified as a moryo, an flesh –eating animal spirit, and was drawn resembling a cat—some also point out the resemblance of the Chinese pronunciation of moryo, kuhasha, as being related to the association of cats with kasha.

In another book, Hokuetsu Seppu ( 北越雪譜; Snow Country Tales, 1837), a story is told—said to come from the Tensho era (1573-1592) in Eichigo province (Modern day Nigata prefecture)—where a funeral is interrupted by a gust of wind and a fireball that comes from the sky. Inside the fireball is a massive two-tailed cat (the calling card of the nekomata) that snatches up the coffin. But the priest attending the funeral beat away the kasha with his staff.

Over time, this cat-form of kasha began to dominate, and other Japanese cat legends became associated with kasha. Like the neko mata and the bakeneko, kasha were said to be transformed house pets that lived an unusual span. Others said it was the presences of corpses that cause the transformation. Cats who jumped over coffins were said to be able to wake the dead. A cat left alone too long with an unattended corpse would transform into a kasha and drag the body away. Fear of the kasha became so great that when someone died the household cats were instantly banished, and coffins were even weighed down with rocks to prevent them from being drug away.

This particular element makes logical sense. Cats eating their dead owners is a real thing. The phenomena is called postmortem predation and, while dogs do it too, cats are well known to waste little time making a meal of their former owner. After a day or two alone with a corpse cats will start to chow down. If a person dies alone, and the corpse is undiscovered for weeks, the family pet might make a nice little feast and leave little left to be discovered. Because of this it doesn’t take too much imagination to see how the flaming chariot that comes from the sky to snatch bodies became mixed with the very real situation of a cat eating a corpse.

Other Kasha

Japan has many other yokai similar to kasha, some even using a variation of the name. The kasha baba is one common variation, which has the same story of someone who snatches corpses from funerals but instead of a cat-like creature it is an old woman. In Kanra-machi in Gunma prefecture there was the legend of the tenmaru that snatched corpses from funerals and graveyards. To protect the dead bodies, caskets were protected by bamboo cages as part of the burial.

Read more yokai magical animal tales on hyakumonogatari.com:

Nekomata – The Split-Tailed Cat

The Tanuki and the White Snake

The Appearance of the Spirit Turtle

,

,  ), Mathew Meyer (

), Mathew Meyer ( ), and–humbly–myself, Zack Davisson (

), and–humbly–myself, Zack Davisson ( ,

,  , upcoming Yurei: The Japanese Ghost).

, upcoming Yurei: The Japanese Ghost).

. Is there a yokai-inspired comic in Seifert’s future? I suggest you keep an eye out on your local comic shop!

. Is there a yokai-inspired comic in Seifert’s future? I suggest you keep an eye out on your local comic shop!