What is a yokai? What is a mononoke? What is a bakemono? Are yurei also yokai? These seemingly basic questions have no precise answers. Almost everyone has their own ideas, and they seldom agree with each other. Because folklore isn’t a science.

Defining these words is like trying to define “monster” or a “superhero.” I have seen (and participated in, ‘cause that’s how I roll) debates on whether the xenomorph from the “Alien” films belongs in a category of “movie monsters.” Some say that because it is an “alien”—and aliens aren’t traditional folkloric monsters—it can’t be a monster. (I disagree.) But the word “monster” isn’t clearly defined. Basically, anything scary can be a monster. So by that token, are ghosts “monsters?” What about “human monsters” like serial killers? Dragons in fantasy movies? When does something stop being a monster? Or start being a monster? What about the Cookie Monster? Or Monsters Inc.?

And how about superheroes? Even though he lacks super powers, Batman is generally accepted as a superhero, but how about Sherlock Holmes? Or Tarzan? Or Gilgamesh, Beowulf, and Heracles? Where do you draw the line? Should the line be drawn at all? Does popular consensus matter?

As you can see, there is no real answer. Just opinions. And almost all of the great folklore researchers have their own opinions. They disagree with each other on the definition and categorization of yokai, on exactly what a yokai is and if a yurei counts as a yokai or not. Almost every book on yokai and yurei begins with the definition of terms—what that particular researcher/writer considers to be a yokai or a yurei.

You just kind of have to pick your camp and decide who makes the most sense to you. Or start your own camp, because that’s valid too. Just don’t expect anyone to agree with you.

Etymology of Yurei and Yokai

Hansho from Osaka Prefectural Library

Like (almost) all kanji, the characters for yurei and yokai originate from Chinese. According to researcher Suwa Haruo, the kanji for yurei (幽霊) first appeared in the works of the poet Xie Lingyun who wrote during the time of China’s Southern Dynasty (5 – 7 CE). The kanji for yokai (妖怪) appeared much earlier, in the classical 1st century Book of Han (漢書) which coincidentally also records the first known mention of the island of Japan. (Strange that the first known use of yokai and the first known mention of Japan appear together—there is some deeper meaning in that!)

Neither word has quite the same meaning in Chinese as it does in Japanese. Chinese uses the kanji 鬼 (gui) to mean ghost, which was imported into Japanese as the word “oni.” And the Chinese usage of 妖怪 (yokai) refers specifically to human beings under some sort of supernatural influence. (This is all according to Suwa Haruo, by the way. I have no personal knowledge of the Chinese language!)

Japan imported both terms, with yokai first appearing in the 797 CE history book Shoku Nihongi (続日本紀 ; Chronicles of Japan Continued), the second of the six classical Japanese history texts. Yokai described an unseen world of mysterious, supernatural phenomena. The term represented something invisible, without form or identity; a mysterious energy that pervaded the deep forests, oceans, and mountains.

In truth, the word “yokai” was barely used at all. Ancient Japan had a more common name for this invisible, mysterious energy—mononoke. The idea of mononoke was something to fear—a mysterious, natural force that could come out any time and kill you, like a lightning strike or a tidal wave. It took the artists of the Heian period to give form to this mysterious energy, and transform the mononoke into bakemono, changing things. And then it took the writers of the Edo period to take these shapes and give them stories. Few of these artists and writers would have recognized their work as “yokai.”

Yokai as a word only came into general use the during the Meiji period, thanks to folklorist Inoue Enryo (1858 – 1919). He founded a field of study he called Yokaigaku, or Yokai-ology. Inoue used the term “yokai” in the same way we would say Fortean phenomenon—meaning any weird or supernatural phenomenon. Wanting Japan to move into the modern world, Inoue used the term “yokai” to point out the foolishness of believing in such things in a scientific age, and vowed to shed light into the dark, superstitious corners of Japan. He hoped to eradicate “yokai” by studying it and explaining it scientifically.

Yanagita Kunio’s Yurei vs. Bakemono

Yokai Dangi cover from Amazon.co.jp

Yokai Dangi cover from Amazon.co.jp

Yanagita Kunio took the next attempt at parsing out the various folklore and coming up with some kind of workable system or definitions. Yanagita put differentiated between “obake/obakemono”—being bound to a particular place, and “yurei”—being able to move freely, yet bound to a specific person. Here’s what he said in his Yokai Dangi (妖怪談義;Discussions of Yokai):

“Until recently there was a clear distinction between obake and yurei that anybody would have realized. To start with, obake generally appeared in set locations. If you avoided those particular places, you could live you entire life without ever running into one. In contrast to this, yurei—despite the theory that they have no legs—doggedly came after you. When [a yurei] stalked you, it would chase you even if you escaped a distance of a hundred ri. It is fair to say that this would never be the case with a bakemono. They second point is that bakemono did not choose their victims; rather they targeted the ordinary masses … On the other hand, a yurei only targeted the person it was connected with … And the final point is that there is a vital distinction regarding time. As for a yurei, with the shadowy echo of the bell of Ushimitsu [the Hour of the Ox, approximately 2-2:30 AM], the yurei would soon knock on the door or scratch on the folding screen. In contrast, bakemono appeared at a range of times. A skillful bakemono might darken the whole area and make an appearance even during the daytime, but on the whole, the time that seemed to be most convenient for them was the dim light of dust or dawn. In order for people to see them, and be frightened by them, emerging in the pitch darkness after even the plants have fallen asleep is, to say the least, just not good business practice.”

Translation from Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai

In Ikeda Yasaburo’s book Nihon no Yurei he almost agrees with Yanagita, seeing two distinct types of yurei. The first kind, as evidenced by the story The Chrysanthemum Vow, show a spirit with a specific purpose and attachment towards another human being. They have the ability to travel, to move “a hundred ri” as Yanagita puts it. The other kind of spirits, as evidenced by The Black Hair, are those spirits bound to a particular place. They may have some sad story keeping them put, but ultimately it is the location that matters.

Ikeda says:

“Usually I just call both types yurei, but it might make sense to make a distinction. You could call the first group—the ones bound to a specific person—yurei, and the second group—those bound to a specific location—yokai. But these groupings are just made for ease of discussion. In truth, the spirit realms are far too complicated for simple classification; any rule or distinction you make is immediately broken.”

Obviously, Ikeda is correct; Yanagita’s distinctions fail the simplest of tests. Look at three of Japan’s most famous ghosts, Okiku (Bancho Sarayashiki), Oiwa (Yotsuya Kaidan), and Otsuyu (Botan Doro). The plate-counting Okiku is bound to her well, and by Yanagita’s definition would be an obakemono and not a yurei. Oiwa is free to travel where she wills, but doesn’t care at all about the Hour of the Ox. When she appears at her husband’s wedding, it is the middle of the day. And the Chinese origin of Otsuyu means that she obeys almost none of Yanagita’s rules, making her neither obakemono nor yurei.

Yanagita was one of Japan’s first folklorists, and a great researcher and gatherer of tales, but I often disagree with his conclusions. Not for any fault of his own; Being the first, he was operating with a limited amount of materials and information, and not able to discuss or cross-reference his findings.

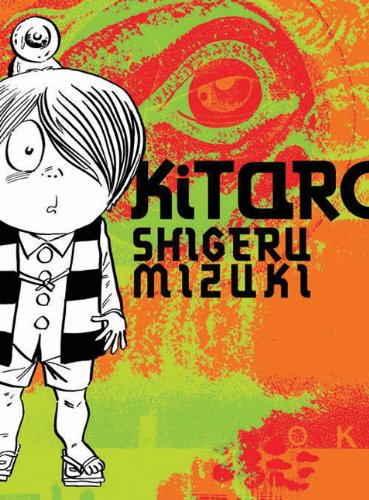

Mizuki Shigeru’s Inclusive Yokai World

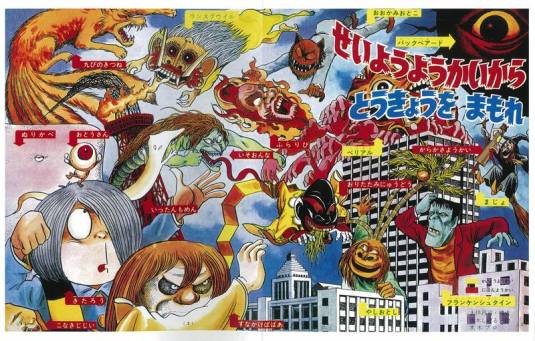

Japanese Yokai battle Western Yokai in Mizuki Shigeru’s Great Yokai War

Japanese Yokai battle Western Yokai in Mizuki Shigeru’s Great Yokai War

Mizuki Shigeru takes a much broader approach, In his Secrets of the Yokai – Types of Yokai he put everything under the general term of “Yokai” (or “Bakemono,” which he considers the same thing”) and then broke it down into four large categories, one of which is “Yurei.” Mizuki started studying yokai seriously in his 60s when he had largely retired from drawing his famous Kitaro

Mizuki’s approach is the most widely accepted today, as seen by the Japanese definition of yokai from Wikipedia:

“Yokai as a term encompasses oni, obake, strange phenomenon, monsters, evil spirits of rivers and mountains, demons, goblins, apparitions, shape-changers, magic, ghosts, and mysterious occurrences. Yokai can either be legendary figures from Japanese folklore, or purely fictional creations with little or no history. There are many yokai that come from outside Japan, including strange creatures and phenomena from outer space. Anything that can not readily be understood or explained, anything mysterious and unconfirmed, can be a yokai.”

I personally fall into Mizuki’s camp—I believe yokai are so much more than just Japanese monsters. In fact, if you look at Toriyama Sekien’s yokai encyclopedias many Japanese yokai did not originate in Japan—they are characters from Chinese folklore or Indian Buddhism added to Japan’s pantheon. And even inside Japan, yokai encompass so much more than monsters. There are yokai winds. Yokai illnesses, Yokai transformed/possessed humans. Pure yokai monsters.

But then again, I am as guilty as anyone for also using the word yokai as a shorthand for Japanese monsters. Because it is convenient, and gets the meaning across in a simple fashion. And sometimes, convenience trumps accuracy. Because folklore isn’t a science.

Yurei and Yokai – Dead Things

Yurei entry from Toriyama Sekein’s Hyakkai Yagyo

Yurei entry from Toriyama Sekein’s Hyakkai Yagyo

Then you get into a whole other area—Are yurei a type of yokai? Or are they something different? Again, there is no universally accepted answer. Yanagita Kunio considered yurei to be yokai, but not bakemono. Mizuki Shigeru considers yurei to be one of the Big Four categories of yokai. Matt Alt calls yurei and yokai out as two separate things in his books Yokai Attack!

To me, this is the easiest question—of course, yurei are yokai. All you have to do is look at the yokai collections from the Edo period. Yurei were always included as entries. Edo period kaidan-shu freely mixed ghost and monster stories. Games of Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai always included strange stories of any type, with no differentiation between yurei and yokai. They were all just “weird tales.”

For that matter, some yokai monsters are in fact dead humans who returned as yokai. Many things can happen to a human spirit after death. They can move on to peace, transform into a yurei and haunt away, or transform into a monster with a life that lasts far beyond their death. Perhaps the most famous example is the Emperor Sutoku who died and was reborn as the Evil King of the Tengu, a story that appears in both the Hōgen Monogatari and Tales of Moonlight and Rain (Translations from the Asian Classics)

. Or there is the massive Gashadokuro, sometimes said to be the assembled bones of people who died of starvation. Or Dorotaro, the spirit of a farmer whose fields were mistreated by his son.

There are many others. Yurei is clearly just one form a human being can manifest as after death. They can become kami. They can become yurei. They can become yokai. All though saying “they can become yokai” is redundant, as they are all yokai.

Religion and Yokai – Degraded and Unworshiped Gods

Another thing Yanagita Kunio says—and this I agree with him on—is that some yokai are the traditional, historical, and forgotten gods of Japan. In his book Hitotsume Kozo he outlines his “degradation theory,” showing how ancient gods are slowly demoted into small-time monsters, and then folktales. He uses the kappa as an example. Once a powerful water deity—and there are still a few kappa shrines in Japan—the kappa was demoted over the centuries to a beastly monster, to something almost harmless, until now it is little more than one of Japan’s “cute character mascots.”

Many yokai also share strong ties with Buddhism. During the Edo period Kaidan Boom, several strange monsters and gods were imported from India and China and recast in roles as Japanese yokai. As with Yanagita’s degradation theory, these once-mighty beings become silly goblins in the Japanese pantheon,

Komatsu Kazuhiko put forward the idea that yokai are sort of the B-List of the kami pantheon, the “unworshiped gods.” It has long been thought that spirits can be transformed into kami via ritual and worship. By that measure, yokai are simply proto-kami, amassed spiritual energy that has managed to take form, but needs the extra boost from human worship to advance to the next stage and become a true kami.

Just as many yokai have no connection to religion at all. Toriyama Sekein created a host of yokai for his books, some of which were just ghostly twists on plays on words or popular phrases. Kyokotsu the Crazy Bones being one of the most obvious examples. A few hundred years later, and these Toriyama-invented yokai are considered just as valid as something like a kappa that is thousands of years older.

Modern Yokai

When you ask “What’s the Difference Between Yurei and Yokai?” you sort of have to decide if you mean historical, or modern. In the Edo period and older, there was absolutely no difference. You go back even further, and yokai and yurei are indistinguishable. But as we move more and more into the modern manga-influence era, where yokai are being used as characters in comics, and the meanings of the words appear to be changing.

I think manga is the biggest influence on yokai today. Comics like Kitaro

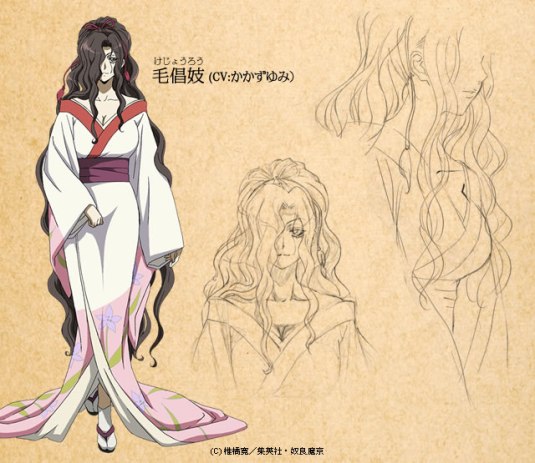

Kejoro from Nura: Rise of the Yokai Clan

Kejoro from Nura: Rise of the Yokai Clan

Those manga yokai are probably just as valid as Toriyama Sekein’s yokai catalog. The definitions of yurei and yokai have changed over the centuries, and will continue to change going into the future. Because “change” is at the heart of yokai. They mold to meet the needs of the current generation. They are mutable.

In his book Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai

Translator’s Note:

This is a long, rambling answer to a question by reader Chiara Leerendix, who was having a debate with her professor on the differences between yurei and yokai. He claimed that yurei were spirits of the dead and related to death and religion, while yokai were just monsters without any deeper meaning or religious connection. Obviously, I disagree with that. But the debate is ongoing.

While I don’t have an exact answer for Chiara, hopefully this will provide her with some good arguing points to take to her professor. Of course, her professor is welcome to respond to this post as well!